A law degree still remains one of the great degrees available to smart, hardworking, dedicated, individuals. The Juris Doctor has both an intrinsic and market value. Like any other degree, its market value is set by a host of factors, including the demand for lawyers, the cost of the degree, the institution from which it was earned, and the price paid. Of course, even more useful to the value of the degree is the skill and quality of the professional holding it. Our profession needs more high quality practitioners, not less.

The legal market is soft, and the legal education market is in peril. At the intersection of that reality sits one of the biggest names in the legal world, Harvard Law. Harvard Law is trying to take down the LSAT and the US News Law School Ranking system. The ramifications of Harvard’s actions will be profound on the quality of the lawyers Schools produce and the debt and burden born by many “graduates.”

Here is how and why Harvard is moving away from the gold-standard LSAT test.

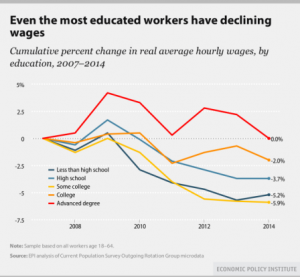

There are too many law schools. They cost too much, and they are woefully short on quality, prospective students. To make matters worse, graduating students are entering a legal market where employment is in decline, and wages are at best stagnant. Sure, the top students from the top schools are still finding jobs, and there is still a market for them. That slice is increasingly smaller.

The demand for lawyers wanes from time to time. That’s not news. However, demand for lawyers and demand for a law degree is now in an 8 plus year decline. That’s not a blip, market change, or slump; that’s the legal world restructuring. The reasons for this are innumerable, and not necessarily ripe for discussion in this op-ed. Let me place reality in two simple examples to set the stage for the discussion, and to help everyone understand the significance of the Harvard Law assault on the LSAT.

At the peak, law school applications nationwide reached nearly 100,000. That was 100,000 applicants to about 200 accredited law schools. In the valley, applications fell to roughly 53,000 nationwide for roughly 200 accredited law schools. Demand has not measurably ticked up, but supply of those law schools remains constant. No other industry would have all competitors surviving such a crash. Of course, universities have many sources of money, including tuition, donors, federal research dollars, and state subsidies. Moreover, just because law applications might be down, doesn’t mean a university isn’t making money somewhere else and using that revenue to support its law school in tough times. So, law schools are hurting, but widespread folding has not yet happened.

The move to eliminate the LSAT is aimed at increasing revenue rather than reducing costs and innovating.

Deans run most law schools. Let me say this about a law school dean. Fewer people are smarter than that select group of individuals. For decades, elevation to the title of Dean reflected a tribute to the legal scholarship accomplishments of career academics. Some became great Deans and administrators, others, not so much. But, until the legal market crashed, Law schools ran themselves and the relative administrative skill of a Dean meant little. Not only did law schools run themselves, but they were powerful profit centers of their respective universities. The world changed on these poor Deans, and some of them, some of their faculties, and indeed some of the university administrations to whom they report, really were not ready for the confluence of events that have shook legal education.

Price was spiraling up as applicants disappeared overnight, and the market for graduates went soft. These Deans hoped it was temporary, but it has not been. Demand for new lawyers plummeted due to many factors, including technology, outsourcing, and weak economic growth. There sat 200 law schools, run mostly by law review writers with limited business, innovation, or management skills.

Now, nearly eight years into this mess, universities and law schools are getting nervous. Deficit spending can’t continue. And, while a few law schools have shifted toward a management style that embraces … well … management, most have not. The primary criterion for new law Deans remain a long list of impressive and relatively useless scholarship. To be fair, universities are prioritizing “fundraising” now for law school deans. Raising money to make new lawyers is not an easy sell, but certainly an essential skill for any new dean.

The legal education industry has not yet embraced change, consolidation, or innovation to reduce its costs. It doesn’t want to do that. In a soft market, with few customers and higher prices, it is instead looking solely at methods to lure new customers. To do so, it is flirting with luring customers who are not qualified, and schools are hoping some of these less qualified applicants will bear the full cost of tuition.

One might argue that the industry has abandoned it ethical obligations and academic standards with respect to applicants in order to become revenue predators.

Law School tuitions are too high, much too high. In fact, nearly no one is paying full freight to go to law school. And, here’s a tip … no one should. If you are paying sticker price to go to law school you probably shouldn’t go to law school … at least not that law school.

Law schools and their universities are pushing hard to find revenue because change is too hard, and the interested parties are too deeply invested to embrace real change. As a result, law schools are creating and expanding offerings of dubious market value. Some are offering various Juris Masters and LLM programs, the overwhelming majority of which add no market value in the legal market. They do, however, pay the bills of the institution, and they transfer the cost of faculty into a debt on students.

Schools make those offering along with steep discounts on tuition in the JD programs in order to draw in legal consumers and increase revenue. As I explained in a much longer piece on the US News Ranking and tuition discounting, it is better to have seats filled at lower initial prices than to have those seats empty. When I say it is better, it is better for the law schools. Whether a student should pay that lower price or attend a particular school involves more factors in the decision analysis.

I still believe law school is a great investment for the right caliber of student at the right price, in the right institution and market.

For law schools, it is better to stay in business than to go out of business. Thus, they face the ethical dilemma of attracting less qualified candidates, or downsizing the tenured faculty in an institution. The single greatest cost in these institutions is tenured faculty. In fact, many universities can’t even get rid of tenured law professors. Some universities must still employ law school faculty even if they close their law school. Now that’s job security. The sunk cost of tenured law faculty is a great albatross around the neck of law schools that are in deep financial discord.

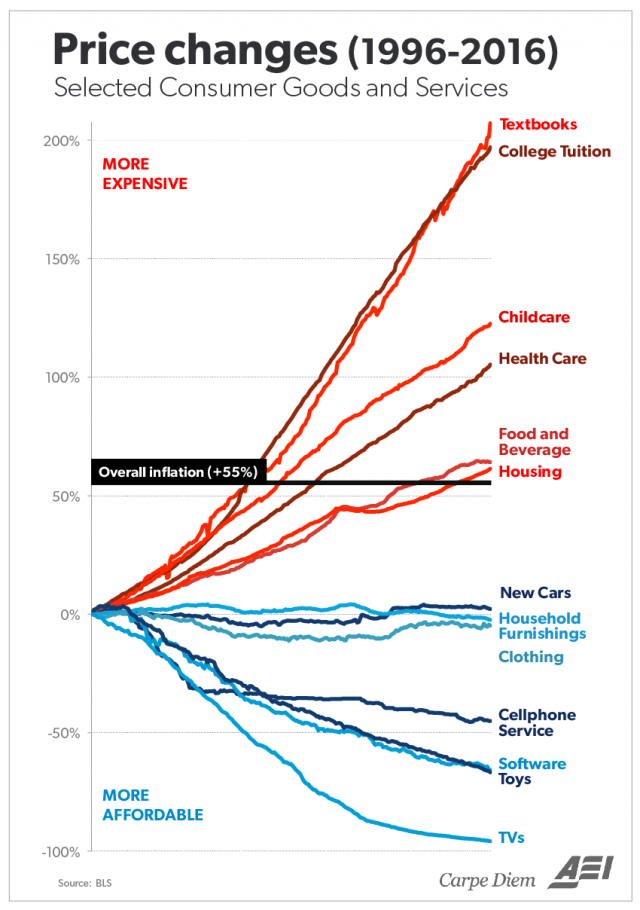

I call these sunk costs the tenure tax. That tax is in every tuition bill in this country, and it is a substantial portion of tuitions that have far out-paced the Consumer Price Index. Lest one think I have little regard for great law professors, nothing could be further from the truth. I have worked with and alongside some of the great legal minds in the industry. I have seen the value of great professors and great scholars. I merely point out that like any industry, when the demand for their services fall, those who are not at the top of the game, or whose skills add the least value, need to be culled from the ranks.

Law schools refuse to do that, and instead they want someone to pay the freight.

So … what does all this have to do with Harvard, the LSAT, the ABA and US News?

Before I go there, I will set the stage with one more example of economic reality in the legal world. I graduated law school as a 34 year-old in 1999. I earned a state court clerkship, and from that landed a job as a litigator with one of the country’s largest law firms. It is now one of the largest law firms in the world. I spent about 30K on my law degree. I graduated from an outstanding regional law school in a strong legal market. Even though my school was second-tier (outside the top 50) at the time, the market was hot and the reputation of the school strong.

If you attend the exact same institution today, you will be in a first-tier law school. The program is outstanding, and every piece of my career shows a loyalty, passion, and advocacy for the institution. However, if you paid the sticker price of that institution, your degree could cost you $120,000 in tuition alone. If my exact same law firm hired you upon graduation into the office I once worked, you would make the same salary I made 18 years ago. Do you see the problem?

This is why law schools are discounting tuition. They must attract consumers by any means possible if they are not going to shut their doors or consolidate, which is the right and proper result in some instances.

Now … Let’s talk about Harvard Law.

Nothing says, “you’re hired” like a Harvard Law degree. (Well, accept maybe a Yale or Stanford law degree). Life is good at the top of the food chain. It should be. Elite students and elite minds can make great lawyers. Harvard has great supply of strong candidates for its law school. However, with applications down so dramatically nationally, even the biggest of guns are not seeing the same strength in their applicant pool. Likewise, Harvard admits some students to its law school on academic numbers that would not support admission of those same students to schools ranked much lower. That’s the right of the institution to do that. However, when Harvard does that, or when any school does that, it must find stronger candidates to offset the lower admission numbers. In short, if Harvard is going to admit a student with a 158 LSAT, it needs to find someone near the “perfect” range in order to offset that admit, lest its median LSAT number fall, and so too does 12.5% of its US News Rank.

Harvard doesn’t like answering to Bob Morse, US News, and it’s deeply flawed ranking. I don’t blame it. Most law deans despise that ranking, though they all know it is the bible among law students.

Harvard has had enough of the LSAT. Harvard is a market maker … not an order taker.

Harvard just kicked the LSAT to the curb. You don’t need an LSAT score to go to Harvard anymore. Just like that, Harvard has announced, essentially, “if we let you in, you are great.” That may be true, and for sure, the market will continue to hire and seek “Harvard Law” graduates. All of this comes with the blessing of the ABA, who must approve such a pilot program.

Harvard’s move might seem self-interested and cocky, but it really is a welcome relief to other law schools. If Harvard ditches the LSAT, why can’t we, goes the thinking. And, if we can ditch the LSAT, then can’t we open more admissions? And, if we open more admissions, then don’t we solve the problem with fewer applicants and deficit budgets? If you read up on all this, you will find legal administrators and law professors praising the repudiation of the LSAT. It’s a barrier to entry, they say.

No … it’s a barrier to revenue and a check on quality. Desperate law schools want that barrier removed because they demand revenue over quality, innovation, or cost reduction. One law school dean likes to use two phrases, nearly regularly. One is, “cash is king” and the other is “Earn our Future.” Both define an industry whose myopic view of reform is only on the revenue side.

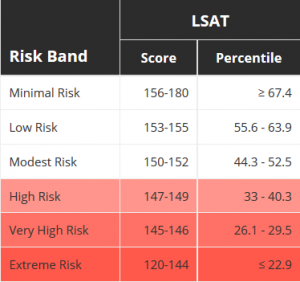

Removing the LSAT from law school admissions is the holy grail of an industry that needs applicants and wants to hide the quality of those it now admits. Grades are nearly meaningless, though US News foolishly assigns them a 10% score in the rankings. Grade inflation, phony majors, BS degrees, and suspect institutions render many “GPAs” valueless. It is the LSAT that has uniformly stood as a constant measure in the industry. Moreover, innumerable analyses of LSAT scores reflect predictable outcomes educationally at certain benchmarks. Scuttling the LSAT removes any meaningful measure of the quality of students at institutions. It opens the market to more tuition payers for the tenure tax.

Sure, it might be right that “Harvard” still gets the best students. But, when Arizona dropped the LSAT requirement, as it has done, what do we really know about the people it is admitting?

The entire push to eliminate the LSAT sits in the lap of several interest groups. The primary people interested in this move are law schools looking to lure students into debt to feed an uncontrolled overhead. Other interest groups include those who think the LSAT is unfair or a burden or hurdle to certain groups for entry to elite institutions. It is a hurdle. It’s designed to be a hurdle so that institutions can make a value judgment on the academic capabilities of their classes. Likewise, the legal market can properly value the intuitions and its graduates.

Harvard and Arizona have both substituted the GRE, a completely different test, for the LSAT. In short, they allow students to apply with one or the other. Though, neither test can be compared properly to each other. The GRE has a purpose, and it test some skills related to the study of law. It’s just an inferior measure, which is why it was never used before.

Harvard doesn’t need more students and money. However, it is sympathetic to interest groups who find the judgment of an LSAT score to be an injustice. Likewise, Harvard doesn’t want to answer to US News, and Harvard is happy to play the market leader for its fellow law schools by ditching the test, opening the door for them to consider doing the same.

It’s a war on the LSAT in the name of increasing revenue and driving up student debt. It is also a war on excellence and standards. Oh, more importantly, Harvard’s pilot gives cover to the ABA as that accrediting body considers scrapping the LSAT for everyone. How convenient.

Also, dropping the LSAT is a war on the US News Ranking.

What is Bob Morse to do?

Morse is the man behind the curtain on the US News Ranking. He’s the grand wizard. If he lets Harvard dictate dropping the LSAT as an admission requirement, he will quite literally spring the entire legal education industry from any accountability. If, however, Morse were to assign the lowest LSAT score to an applicant admitted without an LSAT, he would devastate the median LSAT score of Harvard, causing it to take an unprecedented hit in the Ranking. Will he do that? He could. Harvard doesn’t seem to be concerned, or at least it is betting the Morse doesn’t control its destiny.

At stake, of course, is much more than Harvard. The move to eliminate the LSAT sets up the possibility that desperate schools will admit weak applicants to their institutions, hurting the profession, and leaving weak applicants in deep debt with weak job prospects.

These are problems the ABA claims it cares about. We will see.

The ABA regulation of law schools is remarkably problematic, and even as I draft this the ABA is considering permitting other schools to use the GRE as well for admissions purposes. The ABA gets very little right on legal education. This issue it must get right.

The ABA prohibits law schools from admitting applicants a school knows cannot be successful in that institution. In short, it permits profiteering at the expense of students and quality. The ABA’s record on enforcing this provision is not impressive. If the ABA bows to industry pressure and removes the single best quality control in legal education, it is essentially turning a blind-eye to profiteering under the false and dangerous flag of access.

My “free market” soul yearns to advocate for law schools to sell their respective wares to leveraged kids with the warning of caveat emptor. In reality, doing so imperils life outcomes and places unsuspecting, lower-quality, ill-informed, students on federal loans into the position of subsidizing bloated institutions with a modern version of indentured servitude. With imperfect information, and a decidedly unfair balance of power between schools looking to lure students and students being lured into institutions of dubious quality at dubious prices, now is not the time to reward an industry that has not addressed its cost issues.

In the end, most students at Harvard Law won’t be left in the lurch paying the bill of the tenure tax, but most kids are not going to Harvard, Yale, or Stanford. And, most students ought not be rushing into any law school at just any price.

For better or worse, legal education is a heavily regulated industry. Much of that regulation is damaging and costly to students. None would be more damaging than removing academic standards and converting law schools into revenue predators.

The deadline for seat deposits is just ahead … and I must warn applicants again … caveat emptor.

Author: Richard Kelsey

Richard Kelsey is the Editor-in-Chief of Committed Conservative.

He is a trial Attorney and author of a #11 best-selling book on Amazon written on higher education, “Of Serfs and Lords: Why College Tuition is Creating a Debtor Class”

Rich is also the author of the new Murder-Mystery series, “The ABC’s of Murder,” book one is titled, “Adultery.”

Rich is a former Assistant Law School Dean and Law Professor. At Mason Law Kelsey conceived of, planned, and brought to fruition Mason’s Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property, known as CPIP, drawing on his expertise as a former CEO of a technology company specializing in combating cyber-fraud.

In 2014 he was elected by the graduating class as the faculty speaker at their graduation.

He is a regular commentator on legal and political issues in print, radio and on TV. Rich has appeared on hundreds of stations as a legal expert or political commentator. He provided the legal analysis for all stages of the Bob McDonnell trial and appeal for numerous outlets including NPR and WMAL.

Rich also writes on occasion for the American Spectator and CNSNews.com.

In his free time, Rich is part of the baseball mafia of Northern Virginia, serving on numerous boards and as a little league and travel baseball coach.

His Twitter handle is @richkelsey.